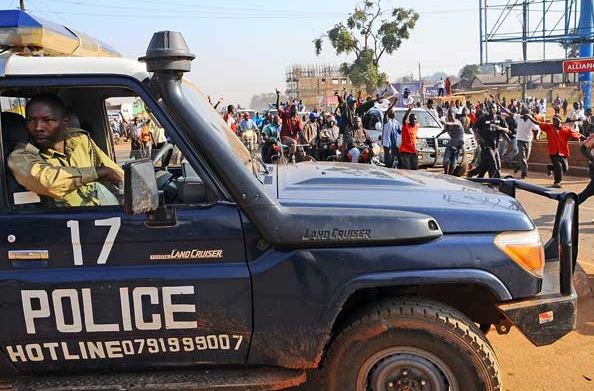

Uganda’s Police Force has rolled out a new mandatory health screening program that will see all suspects tested for HIV and other infectious diseases before they are locked up in police cells, in a move aimed at protecting detainees’ right to health and preventing the spread of infections in detention facilities.

Under the initiative—known as the Breaking the Barriers Initiative—suspects will be screened for HIV, tuberculosis (TB) and malaria at the point of booking, marking a major shift in how police manage public health risks within custody.

Dr. Bernard Ndiwalana, the head of clinical services in the Uganda Police Force, said the screening is designed to establish the health status of suspects before detention and ensure continuity of care, particularly for those living with HIV.

“The data captured enables us to identify suspects who are HIV-positive so that arrangements are made for them to continue with their treatment even while in detention,” Ndiwalana said.

He explained that early detection is critical in police cells, which are often overcrowded and poorly ventilated—conditions that can accelerate the spread of infectious diseases. Suspects found to have malaria are immediately put on treatment to prevent complications such as severe anaemia or death, while those who test positive for TB are isolated and started on medication.

“For TB cases, we isolate suspects in special rooms to enable timely treatment,” Ndiwalana said, noting that although many police cells are small and not ideal for isolation, the force is working to improvise isolation spaces at stations across the country. “These isolation spaces will deter the spread of contagious diseases among suspects during detention.”

The police have also introduced special medical registers at stations to capture suspects’ health data, which is then shared across institutions in the criminal justice system to ease access to healthcare services during detention and prosecution.

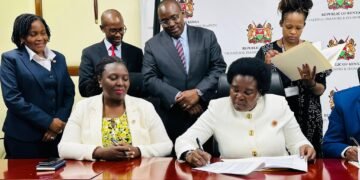

Barbara Masinde, the Chief State Attorney and project coordinator, said the initiative was launched in 2018 after a baseline survey revealed systemic violations of detainees’ right to health.

“The survey showed serious gaps in medical screening at detention facilities, making it necessary to improve access to healthcare for both suspects and inmates,” Masinde said.

She said the impact has been significant, with 91 percent of inmates now reported to have access to quality healthcare services. Masinde added that the compulsory screening measures are backed by Standard Operating Procedures signed by the Inspector General of Police.

“These SOPs allow mandatory screening for TB and other illnesses, including HIV. This breaks the chain of new infections among suspects held in the same cells and allows for early isolation before prosecutions proceed,” she said.

Masinde warned that diseases such as TB spread rapidly in congested cells with poor ventilation, making early and compulsory screening essential. She added that police officers who are first responders during arrests are currently undergoing training to detect symptoms early and ensure suspects are screened promptly.

The police say the program is a critical step toward safeguarding public health within detention facilities and aligning law enforcement practices with human rights and public health standards.