By AFP

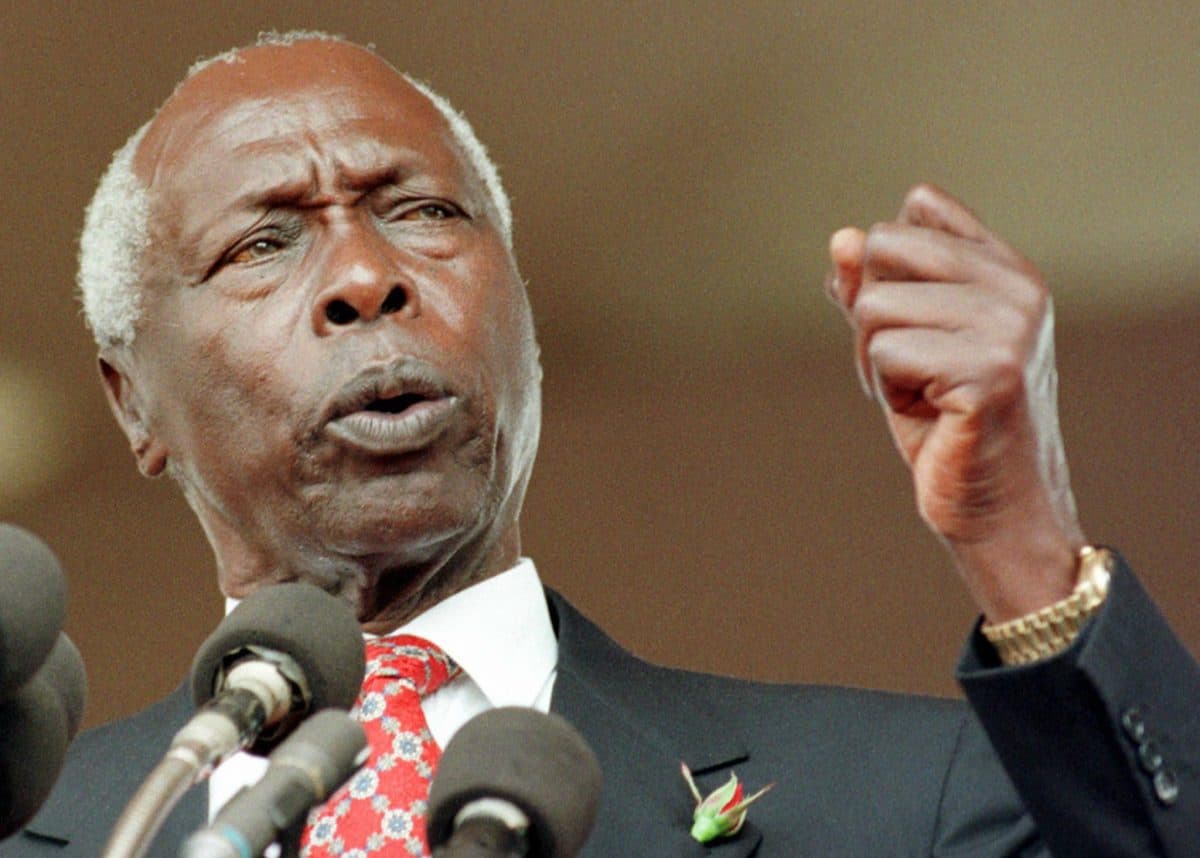

Kenya’s second president Daniel arap Moi took power promising peace, love and unity, but ended up mired in graft scandals, stifling democracy and fanning the dangerous embers of tribalism.

Leading Kenya from 1978-2002 with an iron fist, his 24-year reign was infamous for torture, corruption, the crushing of opposition voices and arbitrary detentions without trial.

Moi died peacefully aged 95 on Tuesday, after he had spent the bitter part of 2019 at Nairobi Hospital, his family said.

Politically astute, he was also accused of encouraging ethnic divisions to further his own political ambitions, tribal rivalries that would leave thousands dead in later years, including contested elections in 2007.

“Ordinary citizens found themselves the target of state repression, and torture and imprisonment became part of the regular engagement between rulers and ruled,” Daniel Branch, from Britain’s University of Warwick, wrote in his book on Kenya’s post-independence politics.

But Moi was also credited with helming a relatively peaceful nation in a region mired by bloody conflicts, including genocide in Rwanda and civil wars in Burundi and Somalia.

Peace at cost of freedom

Brought up in a poor family from the Kalenjin people, in the cattle-herding and farming county of Baringo, some 300 kilometres (185 miles) north of the capital Nairobi, Moi received a Christian education before heading into teaching.

But he was soon drawn to politics, serving in legislative councils under British colonial rule in the run up to independence in 1963, after which he would serve in government under Kenya’s first president, Jomo Kenyatta, rising eventually to be his deputy.

When Kenyatta died in 1978, Moi succeeded to the top job, fighting a tough political battle to secure it from rivals.

Moi’s rise to power heralded Kenya’s final descent into a single party state, with the multi-party system crushed and critical voices tortured or jailed without trial.

A botched coup in 1982 by airforce officers was a turning point, with Moi’s reaction swift and harsh, arresting or sacking dozens.

Lines were drawn and perceived enemies were mercilessly tackled, with those in the regime’s cross hairs including cultural or rights activists such as author Ngugi wa Thiong’o, or environmentalist Wangari Maathai, who later won a Nobel Peace prize.

The 1980s in Kenya were tough times, with university students demonstrating — protests that were quickly crushed — amid runaway inflation, high unemployment and rampant corruption by Moi and a powerful surrounding clique.

Top of the graft scams was the Goldenberg scandal, dealing a crippling blow to the economy, with around a billion dollars siphoned from government coffers under a compensation scheme for export of non-existent gold and diamonds.

As recently as May 2019, a court found Moi guilty of grabbing land, and ordered he pay part of nearly $10 million to the rightful owners of a property he sold.

“Kenyans became ever more resentful of Moi’s government, but because of his ability to work networks of patronage and state institutions to his advantage, the president survived without serious threat to his rule,” Branch added.

Conflicted legacy

By the 1990s, Moi began to cede to international pressure as well as domestic civil society groups to allow a multi-party system, though he firmly maintained it would open the door to chaos, even as he himself manipulated ethnic rivalries.

In 1992, the first multi-party elections in 26 years, erupted into ethnic chaos in which some 2,000 people killed.

“He created the use of targeted ethnic violence as a tool of political management,” said John Githongo, a Kenyan anti-corruption campaigner.

“You can use violence to move populations, change demographics, create a climate of fear so that people vote in a particular way… Moi made it much more organised.”

Moi, who stepped down in 2002 after his handpicked successor — now President Uhuru Kenyatta — lost to opposition leader Mwai Kibaki, would later ask Kenyans for “forgiveness” for the wrongs he had committed.

Out of power, he became a peace envoy for Africa’s troubled Great Lakes region, and also worked to foster peace between rival communities who fought bitterly following the 2007 elections.

In recent years observers had bemoaned the “rehabilitation” of Moi, as the elderly former president had received visits from President Uhuru Kenyatta, his opposition rival Raila Odinga and any politician seeking his blessing ahead of elections.

Kenyatta revived “Moi Day” in his honour in 2017 after it was scrapped in 2010.

“Moi is increasingly being portrayed as a kindly old man who once held the country together,” wrote journalist Rasna Warah in 2018, adding that by the time Moi left office “the country was virtually on its knees”.